Will Trump push Texas Republicans into a dummymander?

A “dummymander” is what happens when Trump tries to gerrymander and fails

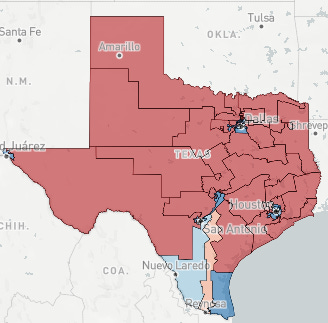

A gerrymander is drawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another. After a successful gerrymander, the offending party will win a number of seats that is predictably and wildly disproportionate to the statewide percentage of votes that the party received. In some States, Republicans have drawn the legislative boundaries so that they can win a majority in the legislature with a minority of the overall statewide vote. In others, they can win a veto-proof supermajority of legislative seats with the barest majority of the overall votes. You get the idea. It’s a sea of red; here’s the estimated congressional map based on existing lines.

A dummymander is a gerrymander gone awry. Gerrymandering involves projecting the partisan vote percentages for each newly-drawn district, but these percentages can change in ways that cause the plan to backfire. As an example, suppose partisan officials draw ten districts. They expect to win nine of them by percentages of 51-49 and lose one district 10-90. That’s an aggressive gerrymander. If their projections do not hold, however, and every district swings by three percentages points towards the opposing party, they will lose all ten districts. That’s a dummymander.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor thought that the possibility of swing elections and backfiring maps meant that gerrymanders were a “self-limiting enterprise.”1 She said that in 1986, however, before mapmakers had access to powerful computers, detailed data sets, and sophisticated models. And back then, politicians and voters were far less polarized and predictable. Gerrymandering is easier today. And yet gerrymanders can still fail.

President Trump has instructed Republicans in the Texas legislature to redraw congressional districts to deliver five additional seats in Congress to the Republican party. Texas’s congressional districts are already gerrymandered—Princeton’s redistricting report card gives them an “F” for partisan fairness.2 To deliver even more seats with the same vote share, the mapmakers will need to take some risks. This size of those risks depends on many things, but Republicans are apparently assuming that no blue wave will materialize, and more specifically:

Partisan turnout will be predictable in 2026 based on past elections.

Republicans will hold or increase their share of the Latino vote in Texas.

Voter migration will not significantly affect district projections.

While Republican operatives will have plenty of data and modeling experts at their side and may well succeed, the wildcard here is Trump himself. His erratic behavior could depress Republican voter turnout and greatly amplify Democratic voter turnout. Trump is the one who claims that elections are rigged, which tends to discourage Republican voters, who take him at his word that the fix is in and voting is pointless. People who can distinguish Trump’s rhetoric from election subversion, on the other hand, are motivated to vote and may turn out in greater numbers.

Trump’s erratic and unlawful conduct may also turn the tide for Latino voters in south Texas, where he picked up more votes in 2024 than his Republican predecessors. Predicting how Latino voters will respond to increased ICE raids and militarization of immigration enforcement is uncertain. And really, the same thing goes for the rest of his policies. Tariffs may yet cause high inflation and unemployment. People may notice that he promoted and signed a bill to cut taxes for the rich and throw people off Medicaid. Maybe firing thousands of government employees will catch up to him.

Lastly, Texas has a lot of incoming residents who are moving away from the high cost of living in blue States. While these people are voting against urban megacenter costs, they won’t necessarily vote for Republican candidates. They might turn out and shift percentages, too.

The bottom line is that while gerrymandering science is making the lines and outcomes easier to manipulate, swings in turnout can still upend the map. Nobody can create those swings like the President. If anyone can turn a gerrymander into a dummymander, he can.

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109, 152 (1986) (O’Connor, J., concurring).

https://gerrymander.princeton.edu/redistricting-report-card/?planId=recL5EF85h0ILukMA. The map that appears above comes from the Princeton redistricting report card website.