I voted “yes” on Proposition 50

I'll explain why

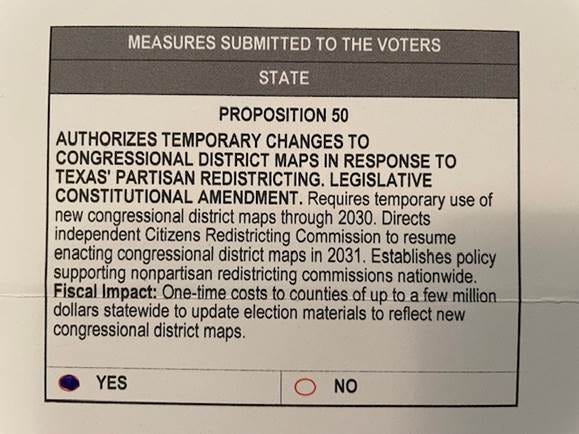

I litigated against partisan gerrymandering for years. It’s wrong. I know that. Back in August, when Governor Newsom proposed to hold a special election for the stated purpose of gerrymandering California’s congressional districts for Democratic advantage, I argued that the proposal was misguided. The California legislature disagreed with me and put Proposition 50 on the ballot.

I voted “yes.”

What has changed since I argued against gerrymandering California? Well, for one thing, when I first wrote about this issue on August 15, Governor Newsom had proposed the ballot initiative, but whether the California legislature would run with his idea and put it on the ballot was uncertain. My initial reaction was that funders and politicians should expend their limited resources on something else. That’s water under the bridge.

Also, I thought more about my assumptions and decided one of them didn’t hold up very well. Specifically, I assumed that gerrymandering California could hurt democracy overall by increasing polarization. A broad pro-democracy majority must attract independents, swing voters, and dispirited Republicans. As partisan polarization increases, forming that broad majority becomes increasingly difficult.

I’m still worried that a purely partisan measure will increase polarization, but after thinking about it more, I don’t know that Proposition 50 will have a significant effect on swing voters or low-engagement voters in 2026 or 2028. Although the initiative is in the news now, the all-important swing voters, low-engagement voters, and independents may not remember it later. If that’s right, then these voters will not penalize Democrats in 2026 and 2028 for having enacted Proposition 50 in 2025, especially outside of California.

After assuming that Proposition 50 will help elect more Democrats to Congress without significantly increasing nationwide political polarization in 2026 and 2028, the hardest question remains: Do the ends justify the means here? Some may think this is an easy question (in either direction), but I think it is a close call.

The first point Prop. 50 proponents make is that Texas did it first, and that California gerrymandering is just a response to Texas gerrymandering. The California legislature wrote this point into the proposition itself (see above). But this retaliatory justification is not satisfying. Usually, the fact that somebody else did a bad thing is not an adequate reason to do the same bad thing. (This is the “two wrongs don’t make a right” point.) But there is a worthy rationale for voting “yes” on Prop. 50. The best reason to do a bad thing is that something even worse will happen in the future if we do not.

Back in my law school years (2003-2006), when the terrorist attacks of 9/11 were still fresh in mind, the ethical challenges of the day included whether to torture terrorism suspects, whether to designate individuals captured far away a traditional battlefield as “enemy combatants” and detain them in Guantanamo Bay, and whether to spy on U.S. citizens without a warrant. I took a class called “The War on Terror,” and we read books such as Michael Ignatieff’s, “The Lesser Evil: Political Ethics in an Age of Terror.” I pulled it off the shelf—the first line of chapter one reads, “What lesser evils may a society commit when it believes it faces the greater evil of its own destruction?”

Today, both Trump’s authoritarian faction and the pro-democracy faction who oppose him believe they are asking and answering Ignatieff’s question about lesser evils. This is why Trump describes Portland, Chicago, and Los Angeles as a war-ravaged hellscapes—he declares the existence of an existential-threat-level rebellion on American soil to justify sending in troops. Those who oppose Trump also see him as an existential threat—meaning that if he is not contained, he will end democracy and destroy our freedoms.

This is not to say that there is an equivalency between what Trump is doing and what those who oppose him are doing—there is none. The difference is that Trump and his enablers are lying, destroying institutions, prosecuting enemies, and deploying military force in American cities without any good reason, while his opponents are accurately pointing out that they are doing all this. The fact that Trump persuaded so many to follow him down a path of lies means that his followers stopped caring about the truth. They’ve thrown in their lot and tribal allegiance will determine the rest without any need to consider facts on a case-by-case basis. We will not do this.

When it comes to Proposition 50—gerrymandering California—there are some mitigating factors that make it less bad. First, it implicitly acknowledges its wrongfulness by calling for federal legislation to establish nonpartisan redistricting commissions nationwide. Second, Proposition 50 is a matter for the voters to decide. In this way, it is democratic with a small “d.” Third, it is limited in scope—it does not abolish California’s independent restricting commission, but instead directs the commission to resume its work in 2030.

On the other side of the ledger, Trump and his loyalists are doing things that are far worse than partisan vote dilution. He is sending people to concentration camps to be tortured, ordering assassinations, deploying troops in American cities, imposing unlawful tariffs, attempting to change the constitution by executive order, refusing to enforce the law, impounding funds, abolishing entire agencies, firing agency heads without cause, prosecuting his enemies, extorting law firms, shaking down media companies, accepting corrupt gifts from foreign powers, attacking allies, and empowering foreign dictators.

While it has long been clear that Trump has governed and will govern as an authoritarian, what makes Proposition 50 a close call for me is the difficulty in assessing the benefit—again remembering that the benefit must outweigh the moral cost of deliberate partisan gerrymandering. The benefit is probably an additional five House seats for Democrats. The likelihood that these five seats will make the difference between majority control and minority wilderness is hard to pinpoint, but I think it is safe to say that other factors are likely to swamp any Proposition 50-specific effect. For instance, if 2026 is a “blue wave” year because of Trump’s unpopularity in a midterm, California gerrymandering will be mostly irrelevant—Democrats would have picked up all those seats anyway.

But what about the scenario where Democrats win control of the house by just one or a few seats? Of course, that would be better for Democrats than the current House, which is 219(R)-213(D), with three vacancies (and one seat is vacant only because Speaker Johnson is delaying the swearing-in for Adelita Grijalva). But if Democrats flip only a few seats in 2026, we are still in dire straits. If that happened, it would mean that voters lived through this administration and barely moved, albeit by just enough to change control of the House. If a president could do all the things described above and barely move the needle with voters, I wonder whether Democratic control of the House would slow him down much.

Still, the benefits of controlling the House are significant. The power to subpoena, hold hearings, impeach, and pass legislation all depend on having a majority. Better to increase the Democrats’ chances of holding these powers so that they can do what they can to slow Trump’s authoritarian advance. Because the risk that Trump will continue to deploy troops and consolidate authoritarian control is so great, and because I no longer assume that gerrymandering California will have lasting adverse effects on swing voters, I think that benefit outweighs the cost. I voted yes.