Does the Stock Market Think That Trump Will Be Good for the U.S. Economy?

Trump will act in areas where he has the most authority and discretion. These areas include appointments, pardons, immigration, international trade, and foreign conflicts. His agenda is to accumulate as much power as possible. Some voters think this is great; others don’t believe that; together, they elected Trump as our next president.

As Trump has already demonstrated, he will appoint loyalists, not intellectual leaders, subject matter experts, or experienced managers. He will pardon allies. When it comes to trade, he will create a tariff-based regime and then dispense exceptions to those who praise and favor him and do business with his or his family’s business entities. Similarly, he will use the United States military to favor foreign leaders who provide a service to him, while abandoning those who do not. Immigration enforcement under Trump will be an exercise in pushing boundaries and crossing lines, all in an effort to reset the limits of what civil society may wearily accept, again, and again.

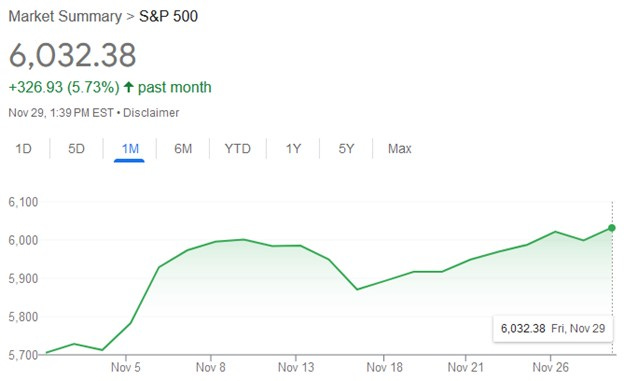

The question I want to pose is: Have markets responded to the election result as though the disruptive acts I’ve just described will either have no effect or be good for the U.S. economy? Or do markets think that the benefits of any forthcoming deregulation and non-enforcement of rules will outweigh the costs of disruption? Immediately, after the election, the S&P 500 jumped in value:

That said, the post-election trajectory is consistent with an overall upward climb that began almost five years ago, after the COVID crash in spring 2020. Here’s the basic Google five-year chart for the S&P 500:

Goldman Sachs suggested that the stock market jumped immediately after the election because investors had not expected that the winner would be known so quickly.1 Still, given what is known about Trump, one might think that a downturn would be the rational market response, for several admittedly broad-brush reasons.

First, the Trump administration’s proposed tariffs will be inflationary. Tariffs are taxes on imports paid by the importer. The importer passes the cost of the tax on to the consumer in the form of higher prices.2 Higher prices on imports enable domestic competitors to raise their prices. Thus, a tariff increases prices on all products that compete with imported goods. As inflation accelerates, the Federal Reserve will increase interest rates, which exerts downward pressure on stock prices.3

Moreover, if Trump imposes tariffs, trading partners will retaliate, which will hurt American exporters. If Congress and the administration provide deficit-financed subsidies to American exporters harmed by retaliatory tariffs (as they have in the past), this too could cause inflation. Even without inflation, American companies that rely on exports or imports are likely to be harmed by tariffs to some degree, decreasing their fundamental value.

Second, stricter immigration controls, including especially any new limits on legal immigration, would decrease the supply of labor, thus increasing the price of labor. While this may be good for workers who compete with legal or illegal sources of immigrant labor, increased labor costs will affect production costs for U.S.-based companies. Such companies will either have reduced profits or pass these increased costs on to consumers in the form of higher prices (or some combination of both). In short, all things being equal, decreased labor supply equals lower corporate profits and higher consumer prices.4

Third, and for an even broader suggestion, consider the possibility that an economy that runs on corruption and oligopoly will produce some winners and losers, but a net loss to the economy as a whole. Companies will divert some additional portion of their efforts to lobbying and seeking favor with the government, whether as a necessary part of winning contracts or to avoid selective enforcement. Those who win the government-industrial complex sweepstakes will not face antitrust enforcement. Monopoly or oligopoly profits for a few, while the rest are squeezed. Most are left worse off.

Fourth, the Trump administration will be chaotic and unpredictable, including in its pay-to-play approach to business and regulation. This leaves companies less able to plan and invest for the future. Lenders and venture capitalists may not be able to assess risk and must incorporate a broader array of potential outcomes into their lending and investment decisions, thus increasing the costs of capital. As the cost of capital increases, companies have less money for equipment and labor. Production slows and the company’s value decreases. And this is on a good day. By staffing his administration with inexperienced loyalists, he will leave the government less able to anticipate and respond to crises such as global pandemics, terrorist attacks, and foreign wars.

Does the rising stock market refute the hypotheses set forth above? Well, one possibility is that everything I’ve just said is wrong. Trump will govern in a stable and predictable manner. He will impose only narrowly targeted and modest tariffs. He will leave legal immigration intact and devote most immigration enforcement to halting criminal activity, e.g., stopping those who cross the border to smuggle in drugs, not to work. His administration will not be any more responsive to lobbying than the last one. Moreover, if federal agencies deregulate in some sectors or make permits easier to obtain, this could decrease some corporate costs. Is this what markets believe?

Maybe. But I doubt it. Rather, I suspect that the Trump victory brought with it a wave of celebration money from supporters and anxious investors, whether because they are happy about the outcome or because they are relieved by the certainty of the result. This could be something like sports betting on the Super Bowl—an event so big that market-moving money is going to slosh around, regardless of the fundamentals.5 At the same time, the executive branch has not actually changed yet. Biden is still President. The economy will remain the “Biden” economy, whatever that may mean, until January 20, 2025, when Trump becomes President.

Investment managers thus can wait and see where the dominoes fall before betting against this market. Who is paying tariffs, receiving subsidies, getting audited, or getting raided? Who has ties to the Trump administration? And when the macroeconomic indicators point toward accelerating inflation and higher interest rates, investment managers can act on this information quickly. Thus, insider edge could or perhaps even should lead investment managers to bide their time and leverage their advantages. In other words, my best-guess answer to my own question is that stock markets are not rationally accounting for the future effects of a Trump administration. They are waiting and watching.

https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/how-trumps-election-is-forecast-to-affect-us-stocks.

For background, see https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-are-tariffs#chapter-title-0-6.

This is the view that a company’s valuation should be equal to the present value of all future profits, which goes down as interest rates go up. See https://www.investopedia.com/investing/how-interest-rates-affect-stock-market.

Here’s one article: https://www.thecgo.org/research/immigration-and-the-stock-market/.

See Nate Silver, On the Edge, at 182 (Penguin Press 2024).