On Venezuela

Twenty-five years after visiting, a military strike

I visited Venezuela with my brother and friends when I was 25 years old. It was not entirely calm and peaceful when we visited. In one town, we had to take a significant detour around a place where protesters had gathered tires and other trash into an enormous pyre on the freeway and set it on fire. But this did not feel threatening to us and the people were friendly. At one unremarkable and seemingly deserted roadside stop, we scrambled down a steep descent to a beach, put on snorkels, and saw the brilliant, colorful, and alive coral. In Los Roques, we traveled by catamaran among lightly submerged white sand dunes and saw all kinds of fish. It was a beautiful place, then, filled with normal people doing ordinary beach things.

We were there in late November of the year 2000. Wireless coverage and internet service was not ubiquitous in Venezuela, and this was before the iPhone anyway. Occasionally, a television in some bar or hotel lobby would remind us that the U.S. presidential election between George W. Bush and Al Gore was still contested, weeks after election day. The unresolved election seemed like a distant and flickering curiosity, not the harbinger of political strife. The terrorist attacks of 9/11 were still about nine months away. In 2000, “war” mainly referred to declared and sustained armed conflict between nations, or so it seemed to me. But that would change.

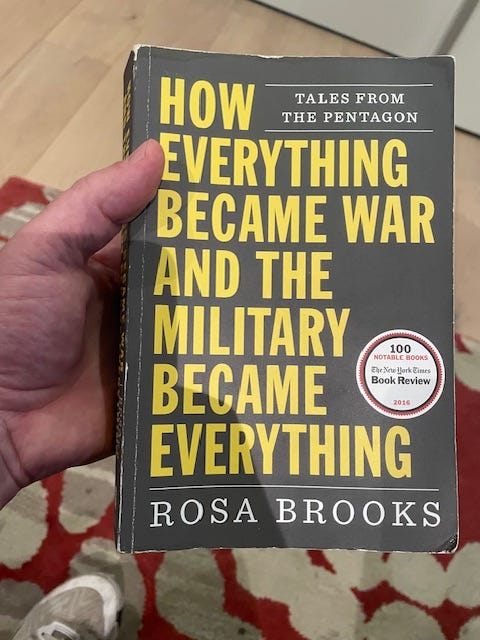

The 9/11 catastrophe and the conflicts that followed altered the concept of “war” in the United States, as Rosa Brooks argues in her book, “How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything.” (Just read it!) Published in 2016, not a single page of it is about Trump. (Refreshing!) It shows how the “war on terror” against nonstate, non-declared combatants in Iraq and Afghanistan has enabled the United States to use the military against virtually any target, for any reason. Terrorists were not state-sponsored; they were usually not actively engaged in combat; they were not found on a battlefield; it was often not clear whether they posed an imminent threat to the United States. But we adapted.

And here we are.

The attack on Venezuela was certainly illegal under statutory law, just as the President’s federalization of the National Guard was plainly illegal, because the required factual predicates were missing in both cases. The War Powers Resolution provides that the President may introduce the United States into “hostilities” only when Congress first declares war, or based on statutory authorization, or because of a national emergency created by an attack on the United States or its armed forces. Congress has not declared war, no statute authorizes the President to attack Venezuela, and it did not attack the U.S. or its armed forces. But a statute governing relations between the executive and legislative branches does not matter if Congress is unwilling to enforce it (via impeachment or power of the purse), and Congress has ignored a long series of transgressions of the War Powers Resolution by both parties.

Because law is and will be irrelevant until Congress decides to impeach Trump and remove him from office, it is more than a little strange that Trump and his allies insist on calling the invasion a “law enforcement operation.” Trump wants to show that law does not exist, not enforce it. When the military bombs a country without its consent, as the United States did in Venezuela, that is an act of war, not an extradition operation. If any country dropped bombs on Washington D.C., killing about 75 people or more, we would treat that as an act of war and fighter jets would be on their way to retaliate one hundred times over.

If pressed about the distinction between law enforcement and war, the administration would ultimately shrug and say that none of these labels matter. As White House deputy Stephen Miller put it, “the real world … is governed by power.” The administration’s official position is that might makes right, which renders any legal or ethical reasoning pointless. The question in this worldview is not whether invading Venezuela was legal or morally sound, but only whether America will benefit.

I don’t see how this is going to end well for the United States. We invaded a country with the stated intent of controlling it and seizing its oil (as recompense for past expropriation, of course). And we are openly justifying the operation on the ground that we are more powerful. Everybody already knew that the United States has the world’s strongest military, but until recently, it stood behind civilian leaders who, in principle, were committed to democracy and human rights. The civilian leaders and their rules—the real ones backed by military force—have changed. By this invasion and declarations accompanying it, the United States announces that violence is the foundation of world order. Democratic aspirations are dead. Teaching this lesson to the world does not seem likely to lead to peace or prosperity for us in the long run.

We can have an idea about this will go for Venezuela. The United States has so far opposed the installation of the winner of the last election in Venezuela (the one that Maduro stole), on the ground that it would be unable to govern, and also opposes new elections for the foreseeable future. It will continue—at our insistence—to be a repressive dictatorship. This choice is unconscionable and treats millions of people as disposable or a kind of non-existent “unpersons,” as Orwell’s 1984 would have it. The thing about visiting a place is that you know on a personal level it is not just lines on a map. On some level, Trump knows this, having flown the world plenty. On another, he really doesn’t see people. He sees oil, golf courses, skyscrapers, casinos. But the people are there, not an abstraction. It would be nice if all those cheering the latest expression of American power remembered that.

(Venezuela, Nov. 2000)